Despite the great scientific and clinical advances of the last decades, diseases transmitted by vectors such as mosquitoes continue to be one of the main threats to global public health. Diseases like dengue are a risk for hundreds of millions of people each year, while malaria still causes more than 400,000 deaths a year. These diseases have been compounded in recent years by outbreaks of Zika, chikungunya and West Nile fever. To the infections transmitted by mosquitoes must be added those of other arthropods, such as black flies, sandflies, chiches, ticks or tsetse flies, which together cause more than 26 million cases annually.

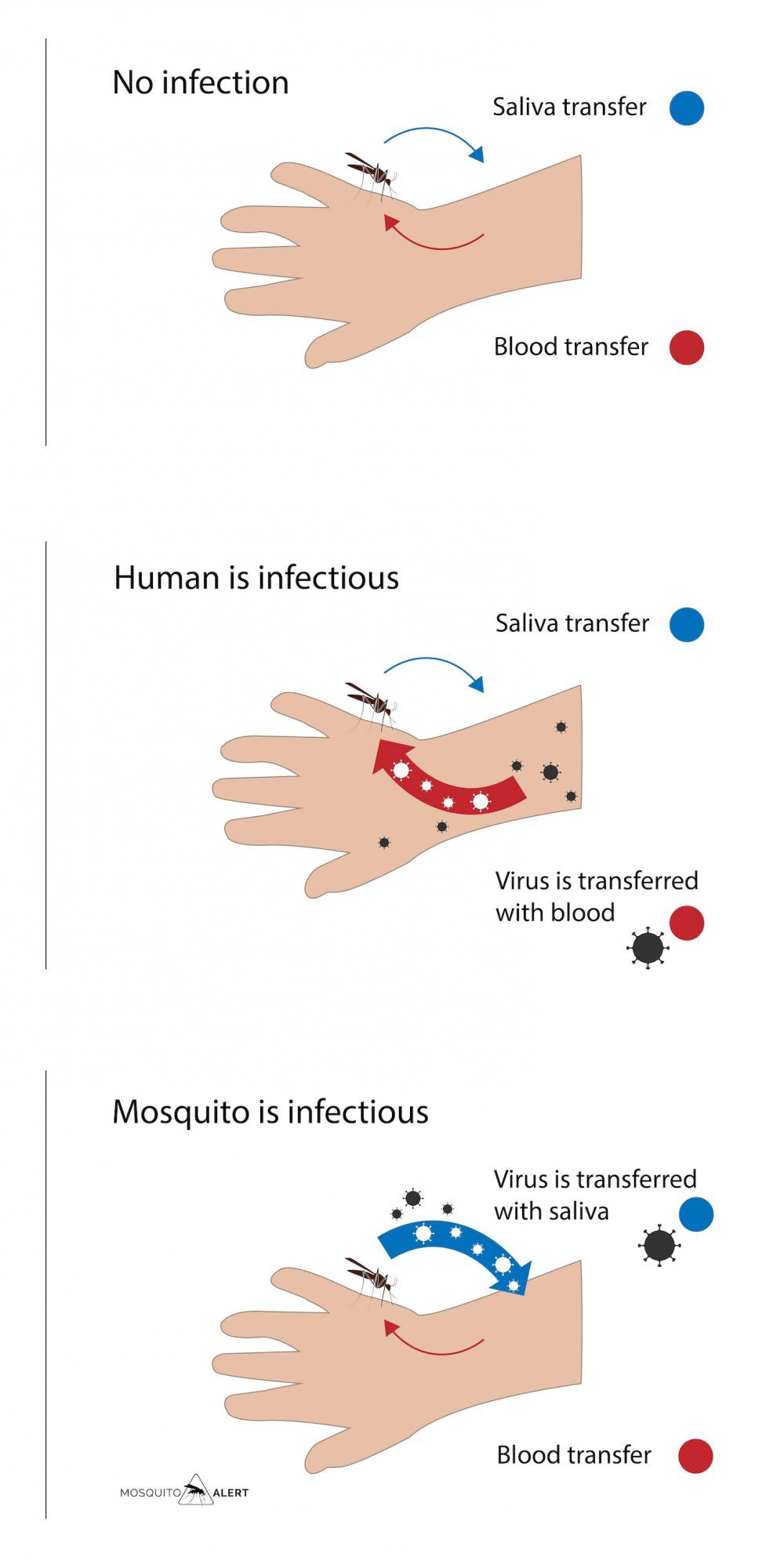

In all these hundreds of millions of cases, the bite is the essential element for the transmission of a disease, from host to mosquito and from mosquito to host. When neither mosquito nor human are infected there is no transmission of any kind, only an exchange of saliva and blood between the two, however, when the human is infectious the pathogen infects the mosquito through the blood it has sucked, so that days later the infectious mosquito can transmit the pathogen to a person by injecting its saliva. The interaction rate between humans and mosquitoes is the most important parameter in determining disease risk according to many mathematical models. However, despite the relevance of the contact rate in the transmission of diseases, there is very little data and very little is known about how the interaction is. This lack of information means that many models end up using the abundance of mosquitoes to estimate risk without taking into account whether a higher density of mosquitoes implies a higher rate of bites, or if this relationship is constant and homogeneous throughout.

Fig. 1. Blood and saliva transfer during a human-mosquito interaction. When the human (host) or the mosquito (vector) is infected by one pathogen, it transfers it to the other, either through blood or saliva. Source: Mosquito Alert CC-BY

Fig. 1. Blood and saliva transfer during a human-mosquito interaction. When the human (host) or the mosquito (vector) is infected by one pathogen, it transfers it to the other, either through blood or saliva. Source: Mosquito Alert CC-BY

There are many variables that suggest that the number of mosquitoes and the number of bites they maintain do not have to maintain a constant relationship. The behavior of vectors, as well as the behavior and habits of people, can change from one place to another, even within relatively small geographic areas such as a city. It is enough to imagine a neighborhood in which there are buildings that have air conditioning and others that do not, where the inhabitants can remain locked in their homes or open doors and windows allowing the entry of mosquitoes. It also affects the existence of gardens that allow more life outdoors and more exposure to mosquitoes, as well as individual behaviors such as the type of clothing that exposes more or less parts of the body to mosquitoes or the use of repellants. There are many factors that determine human-mosquito interaction: both human, environmental and the mosquitoes themselves.

HUMAN FACTORS:

Innate attraction of each person (see how mosquitoes detect us), our behavior (outdoor or indoor activities, we sweat, clothes we wear, use of repellants), human movements (where we move determines that we are exposed to more or less mosquitoes), the abundance of people (the higher the density of people, the more attractive the mosquitoes, but also the greater dilution effect, it can bite the next door), and the socioeconomic factors that determine many of the previous parameters.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS:

For example, if there are alternative hosts in the area (living with pets, birds in the garden or surroundings, etc., towards which mosquitoes can direct their attention), the type of landscape (if it allows there to be breeding places for mosquitoes, have vegetation in which they can rest, etc.), and climatic conditions, in which rain, temperature or wind condition the activity of the mosquito.

MOSQUITO FACTORS:

The physiological status of the mosquito (the female’s need to feed on blood in order to develop her eggs), the innate presence of the mosquito towards a host (mosquito species may have very clear preferences for humans while others are more generalist or even that they do not feel any attraction for humans), and the abundance and density of mosquitoes (the probability of interaction increases when there are many mosquitoes concentrated in an area).

The Human-Mosquito Interaction project

All of this is known to affect the rate of contacts and bites, making it difficult to study. Understanding how outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases arise and spread goes through understanding the dynamics and abundance of mosquitoes, but also the dynamics of the contact rate. Studying contact rates and the factors that determine them is the objective of the project funded by the European Research Council (ERC), Human-Mosquito Interaction Project (h-mip) coordinated by the co-director of Mosquito Alert John Palmer, in which UPF and CEAB-CSIC participate.

The Mosquito Alert application has in its new version a bite module that allows anyone to notify that they have been bitten by a mosquito. You can indicate the number of bites, in which part of the body they have been received, in what type of environment, the place and the time. All this information will allow us to gain knowledge about the spatial and temporal patterns of bites and, in the future, incorporate it into the risk models together with the density of mosquitoes and people.

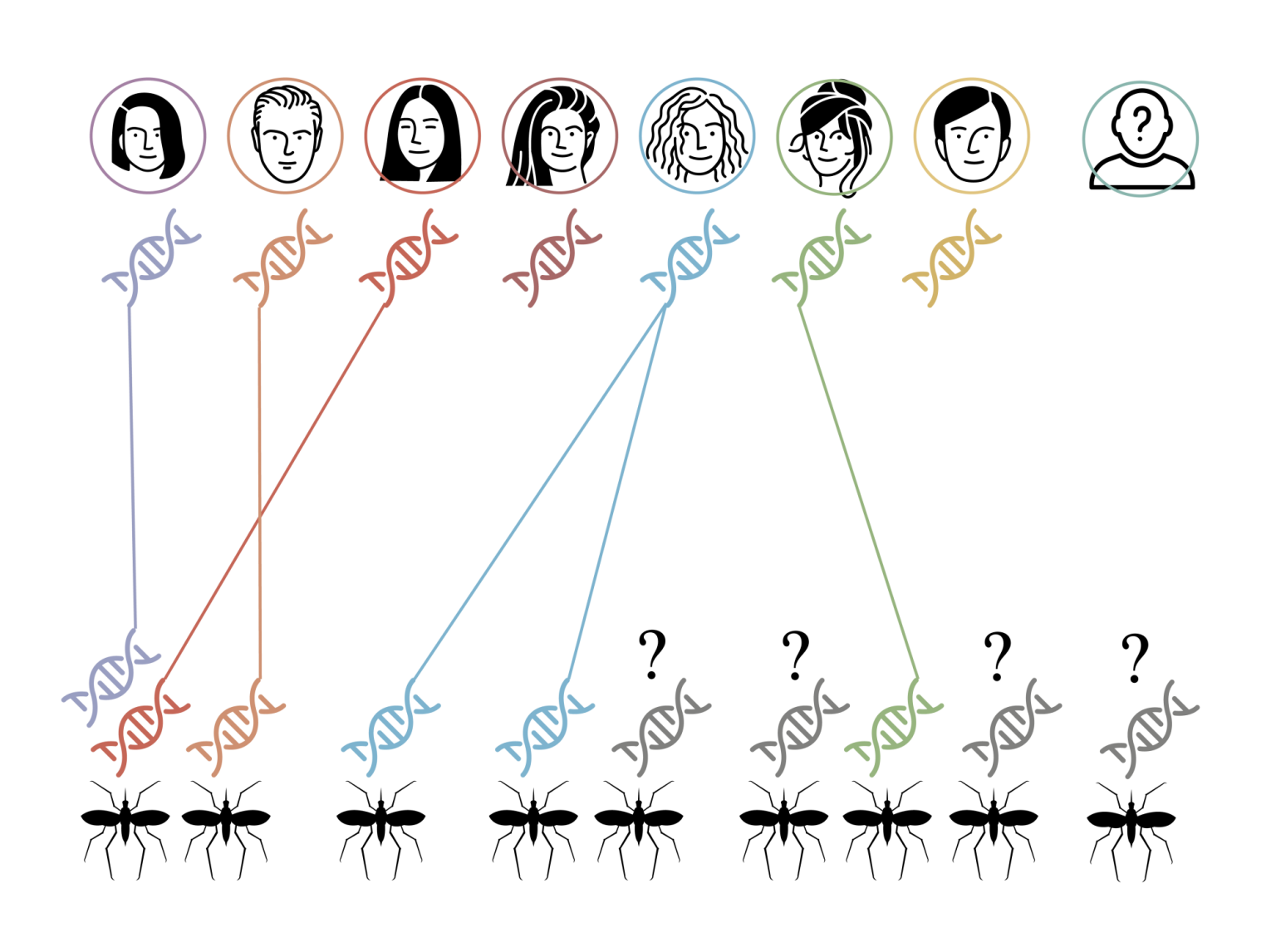

Another objective is to study in greater detail how are the networks of interactions between humans and mosquitoes through which pathogens can flow. How many people does a mosquito bite? Are there people more susceptible to being bitten? The answers to these questions will be solved with the help of genetics, analyzing human blood found in the abdomen of mosquitoes in one area and the saliva of volunteers in the same area. From the DNA obtained from the mosquitoes, dinosaurs like those in Jurassic Park will not be created, but an attempt will be made to reconstruct the network of interactions between mosquitoes and humans.

Another objective is to study in greater detail how are the networks of interactions between humans and mosquitoes through which pathogens can flow. How many people does a mosquito bite? Are there people more susceptible to being bitten? The answers to these questions will be solved with the help of genetics, analyzing human blood found in the abdomen of mosquitoes in one area and the saliva of volunteers in the same area. From the DNA obtained from the mosquitoes, dinosaurs like those in Jurassic Park will not be created, but an attempt will be made to reconstruct the network of interactions between mosquitoes and humans.

Aquesta entrada també es publica al blog de Mosquito Alert

References:

Gao D, Lou Y, He D, Porco TC, Kuang Y, Ghowell G, Ruan S. 2016. Prevention and control of Zika as a mosquito-borne and sexually transmitted disease: a mathematical modeling analysis. Scientific Reports 6: 28070

Thongsripong P, Hyman JM, Kapan DD, Bennett SN. 2021. Human-Mosquito Contact: a missing link in our understanding of mosquito-borne disease transmission dynamics. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 2021: saab011

World Health Organization. 2017. Global vector control response 2017-2030. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland