Today we meet Federica Lucati. She has a degree in Natural Sciences from the University of Padua (Italy) and a Master’s in Natural Sciences. Last June she presented her doctoral thesis entitled: Linking phylogeography and recent dispersal in high mountains: Insights from two Iberian amphibians, directed by Dr. Marc Ventura from the Center for Advanced Studies of Blanes (CEAB-CSIC) and Prof. Rui Rebelo of the Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes (cE3c) of the University of Lisbon.

She is currently a postdoc researcher in the Human-Mosquito Interaction Project funded by the European Research Council (ERC) and coordinated by Prof. John Palmer from the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona and co-director of Mosquito Alert, in collaboration with the Center for Advanced Studies of Blanes (CEAB-CSIC).

Image 1. Federica Lucati

Image 1. Federica Lucati

First and in very general lines, what is it that seduced you about science that led you to embark on a doctorate?

I have always liked science, since I was little I was curious to know the why of things, but the truth is that the opportunity to do a doctorate came by chance from the other side of the world. I spent a season working in the Seychelles as a fieldwork assistant, and my then boss one day told me about a PhD call in Portugal, I applied and after a few months I was at the University of Lisbon with a doctoral scholarship.

Could you briefly explain to us what your doctoral thesis has focused on? What question were you seeking to answer? You’ve got it?

My doctoral thesis has focused on the study of the high mountain populations (especially in the Pyrenees) of two species of amphibians, the Pyrenean newt Calotriton asper and the common midwife toad Alytes obstetricans, through genetic tools. It was about understanding what are the main historical and recent processes that could be responsible for the geographical distribution and the contemporary genetic structure of the two species.

I was able to better understand the role of glaciations and climatic oscillations in the evolutionary history of the study species, and how current dispersal patterns are affected by threat factors such as the introduction of exotic species in the case of the Pyrenean newt and emerging diseases in the case of the midwife toad.

All this information is essential for the development of effective strategies for the conservation of the species.

Image 2. Left: Common midwife toad. Author: Jaime Bosch. Derecha: Pyrenean newt. Author: Claudine Delmas.

Image 2. Left: Common midwife toad. Author: Jaime Bosch. Derecha: Pyrenean newt. Author: Claudine Delmas.

What have been the main difficulties that you have encountered throughout your investigations?

The main difficulties I encountered during my doctorate, which has put my adaptability and resilience to the test. During my first year of doctorate in Lisbon, I had a car accident that forced me to suspend my doctorate for a year and a half.

Then I had to start over from scratch at CEAB. Then there are the typical Ph.D. pitfalls, like failed lab tests that have to be repeated multiple times, data analysis challenges, harsh and critical journal reviewers, and bureaucracy that can cause more problems than the thesis itself.

What things that you know now in relation to the doctorate would you have liked to know before starting the doctorate?

I had been told that the PhD was going to be tough, but I didn’t think I was going to face so many obstacles. The choice of the thesis supervisor is surely fundamental, and I, at CEAB (which is where I finally did most of the doctorate), was lucky to find a very good one.

You tell us that you are currently doing a post-doctorate program. What, then, is your current line of research?

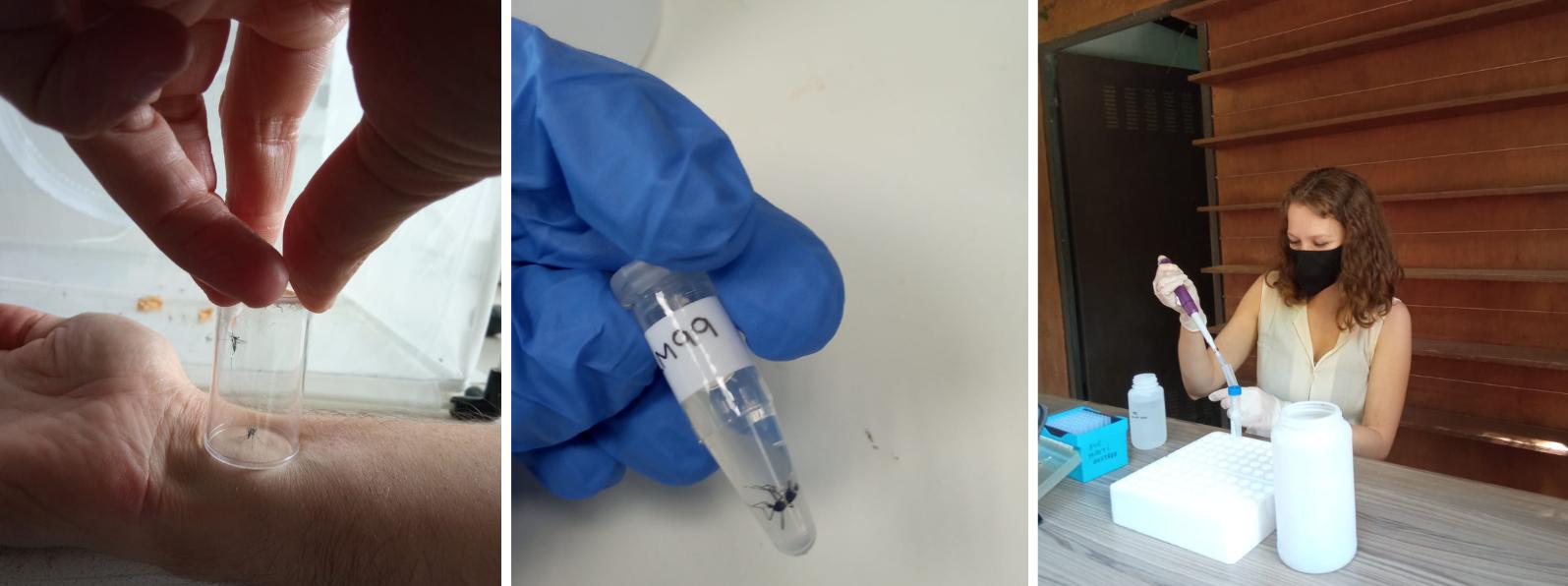

I am in charge of studying the networks of human-tiger mosquito interactions, through genetic analysis of human blood from the stomach of mosquitoes and the saliva of volunteers from a certain region / zone. Mosquitoes are an excellent source of information about people who bite.

By analyzing the blood found in the stomach of mosquitoes, we can answer questions such as, for example: How many people does a mosquito bite? Are there people more susceptible to being bitten?, explains Federica.

On the other hand, people are also an excellent source of information about the mosquitoes that bite them. The genetic profiles found in the blood of the mosquitoes will be crossed with those of the saliva samples of the volunteers, to know if the blood corresponds to any of the volunteers, and thus be able to reconstruct the network of interactions and get to know how many and what mosquito species have bitten each person.

Image 3. Federica Lucati doing experiments with tiger mosquitoes.

Image 3. Federica Lucati doing experiments with tiger mosquitoes.

Why do you think the study of disease-transmitting mosquitoes is relevant? Why is it important to know who they bite or how many times they bite?

The tiger mosquito is an important vector of diseases such as Dengue, Zika or Chikungunya fever. Our results will make it possible to develop more accurate systems for predicting in real time the risk of transmission of diseases transmitted by the tiger mosquito.

Knowing who mosquitoes bite or how many times they bite gives us an estimate of the interaction rate between humans and mosquitoes, which is one of the most important parameters in determining disease risk according to many mathematical models, says Federica.

With the results obtained, we want to contribute to the improvement of current epidemiological models.

How is your day to day at work?

During the doctorate, my work consisted of 3 main stages: collection of samples in the Pyrenees for about 3 weeks in summer, analysis of the samples in the genetics laboratory and data analysis, which is the stage that occupied most of my working hours.

Image 4. Lake Naorte. Author: Marc Ventura, Project LIFE-Limnopirineus

Image 4. Lake Naorte. Author: Marc Ventura, Project LIFE-Limnopirineus

Now, due to the pandemic, I work from home at least two/three days a week. In addition, I spend much less time in the laboratory since my work is more focused on data analysis, writing scientific articles, coordination and communication with the different sectors of the Mosquito Alert team.

What do you like most about your job?

In general, I love the open-mindedness and interdisciplinary, multicultural environment of science. Scientific projects are almost always collaborative, so research offers many opportunities to travel and meet scientific personnel from around the world.

And outside of work, what do you like to do when you’re not around pipettes or in front of the computer?

Outside of work I like to dedicate myself to my extra-work scientific projects, learn new languages (now, for example, I go to Catalan classes), sell things online, travel, go out with my friends/partner.

How do you see yourself in 10 years from now on? Would you like to continue in the world of scientific research?

I don’t usually think much about my future work, I just know that I like science and I would like to continue doing research, although the precariousness in science makes it complicated. I am clear that I want to move up in my work, in the future I would like to lead my own research projects and hopefully my own team, and also have more opportunities to travel and collaborate with different research groups.

If you had to describe the Mosquito Alert project in one word or short phrase, what would you say?

Multidisciplinary and innovative… it’s amazing! 😉

This post is also published on the Mosquito Alert blog.